|

|

AT&T Dataphone

AT&T Dataphone

|

|

1960

AT&T designed its Dataphone, the first commercial modem, specifically for

converting digital computer data to analog signals for transmission across its

long distance network. Outside manufacturers incorporated Bell Laboratories'

digital data sets into commercial products. The development of equalization

techniques and bandwidth-conserving modulation systems improved transmission

efficiency in national and global systems.

|

|

|

|

|

1964

Online transaction processing made its debut in IBM's SABRE reservation system,

set up for American Airlines. Using telephone lines, SABRE linked 2,000

terminals in 65 cities to a pair of IBM 7090 computers, delivering data on any

flight in less than three seconds.

|

|

|

JOSS configuration

JOSS configuration

|

|

1964

JOSS (Johnniac Open Shop System) conversational time-sharing

service began on Rand's Johnniac. Time-sharing arose, in part, because the length of

batch turn-around times impeded the solution of problems. Time sharing aimed to bring

the user back into "contact" with the machine for online debugging and program

development.

|

|

|

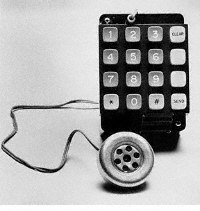

Acoustically coupled modem

Acoustically coupled modem

|

|

1966

John van Geen of the Stanford Research Institute vastly improved the

acoustically coupled modem. His receiver reliably detected bits of data

despite background noise heard over long-distance phone lines. Inventors

developed the acoustically coupled modem to connect computers to the telephone

network by means of the standard telephone handset of the day.

|

|

|

|

|

1970

Citizens and Southern National Bank in Valdosta, Ga., installed the country's

first automatic teller machine.

|

|

|

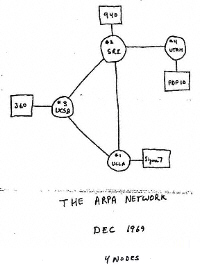

ARPANET topology

ARPANET topology

|

|

1970

Computer-to-computer communication expanded when the Department of Defense

established four nodes on the ARPANET: the University of California Santa

Barbara and UCLA, SRI International, and the University of Utah. Viewed as a

comprehensive resource-sharing network, ARPANET's designers set out with

several goals: direct use of distributed hardware services; direct retrieval

from remote, one-of-a-kind databases; and the sharing of software subroutines

and packages not available on the users' primary computer due to

incompatibility of hardware or languages.

|

|

|

Wozniak's "blue box"

Wozniak's "blue box"

|

|

1972

Steve Wozniak built his "blue box," a tone generator to make free

phone calls. Wozniak sold the boxes in dormitories at the University of

California Berkeley where he studied as an undergraduate. "The early

boxes had a safety feature -- a red switch inside the housing operated by a

magnet taped onto the outside of the box," Wozniak remembered. "If

apprehended, you removed the magnet, whereupon it would generate off-frequency

tones and be inoperable ... and you tell the police: It's just a music

box."

|

|

|

Ethernet

Ethernet

|

|

1973

Robert Metcalfe devised the Ethernet method of network connection at the Xerox

Palo Alto Research Center. He wrote: "On May 22, 1973, using my

Selectric typewriter ... I wrote ... "Ether Acquisition" ... heavy

with handwritten annotations -- one of which was "ETHER!" -- and with

hand-drawn diagrams -- one of which showed `boosters' interconnecting branched

cable, telephone, and ratio ethers in what we now call an internet.... If

Ethernet was invented in any one memo, by any one person, or on any one day,

this was it."

Robert M. Metcalfe, "How Ethernet Was Invented", IEEE Annals of

the History of Computing, Volume 16, No. 4, Winter 1994, p. 84.

|

|

|

|

|

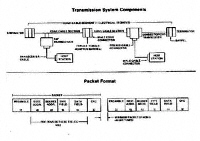

1975

Telenet, the first commercial packet-switching network and civilian equivalent

of ARPANET, was born. The brainchild of Larry Roberts, Telenet linked

customers in seven cities. Telenet represented the first value-added network,

or VAN -- so named because of the extras it offered beyond the basic service of

linking computers.

|

|

|

|

|

1980

John Shoch at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center invented the computer

"worm," a short program that searched a network for idle processors.

Initially designed to provide more efficient use of computers, the worm had the

unintended effect of invading networked computers, creating a security threat.

Shoch took the term "worm" from the book "The Shockwave

Rider," by John Brunner, in which an omnipotent "tapeworm"

program runs loose through a network of computers. Brunner wrote:

"No, Mr. Sullivan, we can't stop it! There's never been a worm with

that tough a head or that long a tail! It's building itself, don't you

understand? Already it's passed a billion bits and it's still growing. It's

the exact inverse of a phage -- whatever it takes in, it adds to itself instead

of wiping... Yes, sir! I'm quite aware that a worm of that type is

theoretically impossible! But the fact stands, he's done it, and now it's so

goddamn comprehensive that it can't be killed. Not short of demolishing the

net!" (247, Ballantine Books, 1975).

|

|

|

|

|

1985

The modern Internet gained support when the National Science foundation formed

the NSFNET, linking five supercomputer centers at Princeton University,

Pittsburgh, University of California at San Diego, University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign, and Cornell University. Soon, several regional networks

developed; eventually, the government reassigned pieces of the ARPANET to the

NSFNET. The NSF allowed commercial use of the Internet for the first time in

1991, and in 1995, it decommissioned the backbone, leaving the Internet a

self-supporting industry.

The NSFNET initially transferred data at 56 kilobits per second, an improvement

on the overloaded ARPANET. Traffic continued to increase, though, and in 1987,

ARPA awarded Merit Network Inc., IBM, and MCI a contract to expand the Internet

by providing access points around the country to a network with a bandwidth of

1.5 megabits per second. In 1992, the network upgraded to T-3 lines, which

transmit information at about 45 megabits per second.

|

|

|

ARPANET worm

ARPANET worm

|

|

1988

Robert Morris' worm flooded the ARPANET. Then-23-year-old Morris, the son of a

computer security expert for the National Security Agency, sent a

nondestructive worm through the Internet, causing problems for about 6,000 of

the 60,000 hosts linked to the network. A researcher at Lawrence Livermore

National Laboratory in California discovered the worm. "It was like

the Sorcerer's Apprentice," Dennis Maxwell, then a vice president of

SRI, told the Sydney (Australia) Sunday Telegraph at the time. Morris was

sentenced to three years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a

fine of $10,050.

Morris, who said he was motivated by boredom, programmed the worm to reproduce

itself and computer files and to filter through all the networked computers.

The size of the reproduced files eventually became large enough to fill the

computers' memories, disabling them.

|

|

|

Berners-Lee proposal

Berners-Lee proposal

|

|

1990

The World Wide Web was born when Tim Berners-Lee, a researcher at CERN, the

high-energy physics laboratory in Geneva, developed HyperText

Markup Language. HTML, as it is commonly known, allowed the

Internet to expand into the World Wide Web, using specifications he developed

such as URL (Uniform Resource Locator) and HTTP

(HyperText Transfer Protocol). A browser, such as

Netscape or Microsoft Internet Explorer, follows links and sends a query to a

server, allowing a user to view a site.

Berners-Lee based the World Wide Web on Enquire, a hypertext system he had

developed for himself, with the aim of allowing people to work together by

combining their knowledge in a global web of hypertext documents. With this

idea in mind, Berners-Lee designed the first World Wide Web server and browser

-- available to the general public in 1991. Berners-Lee founded the W3

Consortium, which coordinates World Wide Web development.

|

|

|

|

|